Colouring Outside the Lines: Art as Literacy in the English Classroom

By Sunaina Sharma

As English teachers, we constantly seek ways to deepen student thinking and engagement—especially in an age when traditional literacy practices alone may not fully reflect how students process and communicate ideas. Over the years, I’ve started to rethink what counts as “writing” and what counts as “text.”

What if visual expression wasn’t just enrichment or an extension activity—but a legitimate way for students to show their thinking?

This idea came to life when I noticed students doodling in class—not as a distraction, but as a way to process ideas. Rather than ask them to stop, I started asking myself: How might art support literacy, engagement, and analysis in English class?

The result has been powerful. Here are three strategies that can be adapted to any English classroom, regardless of grade level or course type.

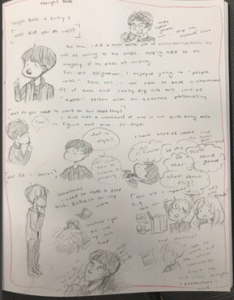

Thought Books: Visual Journals for Reflection and Metacognition

In any English course, we ask students to reflect—on texts, on themes, and on themselves as learners. I began using “Thought Books” as a tool to help students process ideas throughout a unit. Originally, I envisioned these as written journals. But once I opened up the format—allowing students to include sketches, diagrams, and symbolic illustrations—the depth of thinking expanded.

Some students created graphic metaphors to represent their growth. Others illustrated personal connections to texts. By making the mode flexible but holding firm on the learning goals, students felt ownership—and their reflections became more authentic.

Try it: Invite students to respond to a reading using both words and images. Ask them to represent a character’s transformation, or their own evolving opinion on a theme, using symbolic visuals alongside brief annotations.

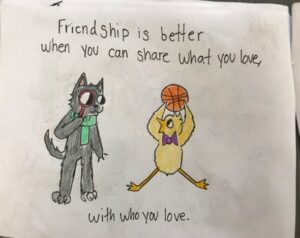

Children’s Books: Visual Storytelling for Any Text

You don’t need to be in a creative writing course to have students engage in storytelling. In fact, writing a children’s book is one of the most accessible—and surprisingly rigorous—ways to consolidate understanding of a complex topic.

In my classes, students have used this approach to explain the plot of a Shakespeare play, break down persuasive techniques for younger readers, or distill the message of a nonfiction article. Students identify criteria for a strong children’s book, co-create a rubric, and then write and illustrate their own.

Try it: After reading a novel or a news article, have students create a children’s book version of the key message. This can be done individually or in pairs, with a focus on clear communication, visuals, and audience awareness.

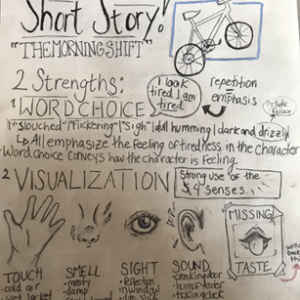

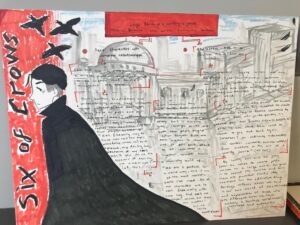

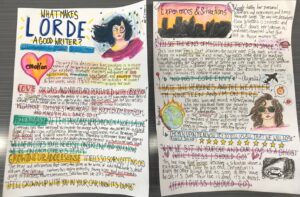

Graphic Essays: Rethinking the “E-Word”

Let’s be honest: the word essay often brings a collective sigh from students. But what if we kept the critical thinking and swapped the structure?

The graphic essay format maintains the rigor of a traditional essay—students develop a thesis, locate evidence, and organize their ideas—but presents it through images and layout. Students must consider visual metaphors, design, and reader engagement while still proving their argument.

What emerged were stunning pieces that demonstrated analytical depth and creativity. It’s not about eliminating the essay—it’s about rethinking how students can express their thinking.

Try it: After a unit, ask students to create a one-pager or graphic essay representing their argument about a character, theme, or issue. Use criteria from your traditional essay rubric, but add categories for visual symbolism and layout.

So, What? What Did Art Really Do?

Integrating art into my English classroom has done more than make assignments look pretty. It has:

- Improved thinking: Students made more intentional choices when tasked with representing ideas visually.

- Increased pride: They were eager to share and celebrate each other’s work.

- Boosted engagement: Even reluctant writers found ways into the task.

- Balanced strengths: Visual thinkers supported verbal ones, and vice versa—building a stronger classroom community.

Most importantly, students saw literacy as something bigger than just writing paragraphs. They saw it as meaning-making.

Final Thoughts

This isn’t just for the artsy kids or the creative courses. Whether you’re teaching persuasive writing, media literacy, short stories, or Shakespeare, integrating art can support comprehension, communication, and critical thinking.

Art doesn’t replace literacy—it expands it. It invites students to think symbolically, communicate more deeply, and see their work as something meaningful and worth sharing.

Let’s give students more ways to show what they know. Let’s make space for visuals alongside vocabulary. Because when students can express themselves in more ways, they often understand more—and care more—too.

Dr. Sunaina Sharma has been a secondary teacher for over 20 years and was an in-school program leader for 10 years. She strives to put the learner’s needs at the forefront of program planning, classroom teaching, and professional learning so that students are participating in authentic and relevant knowledge construction. Her doctoral research centered on understanding how to leverage digital technology in the classroom to increase student engagement. She also is an instructor and practicum advisor in a Bachelor of Education program where she uses her classroom experience to prepare future educators for their role.